By: Veronica Harper

Utah is a beautiful state with gorgeous views. There are so many reasons people are drawn to this state. We have a rich history, the people are welcoming, we are a conservative state with conservative principles, religious, and our elected officials in the legislature serve the will of the people. At least that is what they want us to think.

If you were paying attention to what was going on during the legislative session, you may have asked yourself why bills get passed when there is so much opposition. You may have asked why certain legislators mock the public by performing little stunts that gaslight the people. For a rundown on some of the ways the public are mocked please watch our review of the 2022 session. Aren’t our legislatures elected to serve the will of the people? Do they placate us, the people, while serving their own needs? Like you, I have been asking a lot of questions. The reason I started getting involved was because I had questions that I wanted answers to. The more I started asking, the more I realized our elected officials (not all of them) were not listening to the people. As I started learning how to navigate the bill reading process, I could not help but think that so many of the bills that were passed in the 2023 legislative session were rife with challenges from the public. If not corrected, they can and will affect Utah citizens in a long-term negative way.

If you have ever been up at the capital during the legislative session, I am sure you will agree how quickly things progress. You may even question how so many bills can get passed when our legislators barely have time to read the bills they sponsor, let alone the hundreds of other bills in the que. They may pass bills that have been sold to them as clean up bills, to protect the people, surveillance to fight crime, save the Great Salt Lake, conserve our resources or any number of key phrases that are great sound bites. This was the reason I started writing about special districts. The rise of special districts and the power developers hold over the people should concern every one of us.

This is how seemingly innocent bills get passed without any real discussion. Look at House Bills (HB) 22 and HB77. They are good examples of a “clean up bill”. These two bills were tied together because it would have been too massive to have it be one bill. Both bills together, changed the name of local district to special district. This small but significant change allowed federal money to pour into the state. To quote from a meeting “Greater Salt Lake Municipal Services District – Board of Trustees” Meeting Date: 02/22/2023

“House Bill 22 is one of two bills where the original sole purpose of the bills was to change local district to special district wherever it appears in the Utah code. And that ended up requiring more than 800 pages of bill language, which is why they cut it into two separate bills. The reason for that I think everyone is aware of, when ARPA funding was being considered at the federal level, there was federal legislation to provide money to assist local units of government in reacting to COVID and other problems. The problem with those bills is they use the language special district because that’s what our types of entities are called in every other state except the state of Utah. And the national special districts coalition was able to amend at least one of those bills so that it would include Utah’s local districts.”

“local districts have been local districts for 15 years or so, because before that we were special districts. There was an effort to try to draw a more clear line between special service districts which are a different kind of local governmental entity from the rest of the so-called special districts which are the ones that are independent. And now local districts in the future they will be independent special districts.“

And the third item that was changed, is an admission of intention, “this bill basically will take the control of the district away from the county commission.”

From my previous blogs, Shadow Government Series, you have read that special districts are a government body that has the power to tax the people but are not accountable to the people. Doesn’t that give you warm and fuzzy all over? Once I started digging into this mess, I realized there were times when I walked away in disgust because this process is complicated and confusing. I also realized this is how things can go unchecked if people walk away and stay away. Hence the reason I keep subjecting myself to this pain.

I wanted to look at the 2023-2024 State budget for Utah to see what I could find regarding money for special districts. There seemed to be an accounting of everything but special districts. I searched through the 572-page document and could not find anything pertaining specifically to special districts. Granted, they may be named something specific that I am not aware of so there may, indeed, be an accounting of them in the document.

Shifting gears, I decided to check code to see if I could ascertain the process for the bonds.

17B-1-103 Limited Purpose Local Government Entities – Special Districts

|

(2) |

A special district may:

|

Source: Limited Purpose Local Government Entities – Special Districts

A special district is a government body that can do all the above. I wanted to find out more about the bonding process because I am aware that Public Infrastructure Districts (PID) can do the same. You can check out this article about PIDs and their ability to create bonds. PIDs can tax the people as well as special districts, and they can also create PIDs within their structure. That begs the question, could special districts assess a tax on the people by way of the PID? Are they able to create multiple PIDs within a special district? If so, would it be possible to collect the money from the PID without being accountable to the people? Would this provide a way for taxpayers to be double taxed? Special districts are also able to issue bonds.

Source: Special Service District Bonds

The most common form of bond financing is Tax Increment Financing (TIF).

Bond Financing- This is the most common form of TIF, in which a local government issues bonds backed by a percentage of projected future (and higher) tax collections caused by increased property values or new business activity within the designated project area. In this case, bond proceeds pay for present-day public improvements in the first year. These are projected to create the economic conditions leading to incremental increases in tax revenues, which can take place over a period of 15–25 years. Many bonds are revenue-backed; that is, they are not backed by the full faith and credit of the sponsoring government. Others require the backing of a general fund in order to access cost-effective bond terms. This means that the municipality bears the risk of repayment.

Source: https://urban-regeneration.worldbank.org/node/17

In an article by the Utah Taxpayers Association, a legislative audit uncovered some problems with Tax Increment Financing. The report was presented by the Office of the Legislative Auditor General to the September 2022 interim hearing of the Legislative Audit Committee. They recommended several items to be implemented to “protect taxpayers” from problems associated with TIF.

- First, they recommend that guidance on managing unexpended TIF funds once a collection period expires be included in statute, as is the case in neighboring states of Colorado and Wyoming. Once a project has been completed or if excess tax revenue is created, these funds should be required to be distributed back to the taxing entities. In the study done as part of LAG’s audit, five of the ten projects studied had significant fund balances – in the case of Sandy City South Towne Ridge, collected tax revenues exceeded the budgeted amount by almost 293%. This puts an unfair burden on taxpayers and could be avoided by a simple statutory change requiring that funds be redistributed back to the taxing entities once the TIF collection period expires.

- The second recommendation is that local agencies be legally required to make financial information publicly available for each project area, including receipts, expenditures, account balances and fund transfers. Currently, agencies are required by statute to report general TIF financial information (i.e., a summary of all TIF projects rather than individual projects) to the Go Utah database; however, more than 40% of agencies are non-compliant with this requirement, and no penalty is imposed. Additional accountability would allow for ease of auditing and oversight and reduce the risk of misuse of funds and deceptive practices. Given that taxpayers are paying for these projects, it is important that they have access to accurate and detailed information on how the money is spent.

- The final recommendation is that local governments be required to conduct a thorough “but for” analysis before authorizing the use of TIF. This is the standard in other states and ensures that TIF is used sparingly and deliberately. Utah does require an analysis of the anticipated public benefit of developing the area but does not require agencies to provide evidence that redevelopment would not occur “but for” the incentive of TIF. Taxpayers would benefit from agencies being required to provide substantial evidence of the need for investment since it is likely that not all proposed projects would pass the “but for” test.

Source: Audit uncovers problems with TIF

Another type of bond financing for special districts is green bonds. These appear to be more questionable.

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, Green bonds are,

A fixed income debt instrument in which an issuer (typically a corporation, government, or financial institution) borrows a large sum of money from investors for use in sustainability-focused projects. Green bonds work similarly to a traditional bond issuance, except the funds are slated for use in energy efficiency, renewable energy, or other projects that meet certain sustainability requirements, often formalized in a green bond “framework” developed by the issuer. Green bonds typically involve one or more third-party firms to underwrite, certify, and monitor the bond issuance.

Source: Green Bonds

I bolded some words for you to pay attention to. Is there another global organization that uses language like this? Hint: un.org

Sustainability requirements are code for environmental, social, governance (ESG), which is a way to ensure companies are “encouraged” to adhere to the sustainable development goals (SDG). It looks to me like green bonds would fit nicely into the SDG agenda. Check out this article and let me know what you think about it.

Source: The SDGs must become the DNA of business strategy and management

Utah has been using something similar for some time. The University of Utah implemented an internal green revolving fund for energy efficiency projects in 2007.

“The new fund would tie energy efficiency projects to the office’s budget, allowing the office to reinvest the generated project savings into future projects without having to seek approval behind higher priority budget items, like breakdowns and deferred maintenance.”

The word green bond is not stated specifically; however, evidence suggests that is what they are. For example,

the Chapman law firm “served as counsel to the underwriters in a $478.43 million public offering of green bonds, which will be used to finance several new energy efficient construction projects at the University of Utah including multi-use, living/learning center to foster resident collaboration: new student housing, a mental health translational research facility, and an innovative community-focused hospital complex in West Valley City. Chapman partner Eric Hunter led the deal team.”

Based on the evidence, it seems reasonable that the “internal Green Revolving Fund (GFR) would qualify as a green bond. Was it legal for them to divert?

“funding from the initial M&V to initiate an Energy Management Fund – a revolving fund that established a dedicated budget for energy projects, using saving to continually reinvest in future projects.”

The University of Utah also stated,

Over six years, these projects would return $1.54 million annually in net excess savings, $1.25 million of which went toward repaying current financing and $293,000 of which returned to a larger facilities budget as savings.

Are they still taxing the public based on the initial bonds? By their own admission, they are diverting the savings into the GFR. Would the “savings” actually be considered refundable to the taxpayers? These questions are worthy of discussion and should be answered.

Source: U of U Internal Green Revolving Fund They have since tried to hide the page from public view which really says something.

University of Utah Green Bonds

Do their procedures align with the Policy Statement: Public Infrastructure Districts when issuing bonds? According to the evaluation criteria in the document, one of the criteria is the following:

A District’s sole method for public finance of infrastructure is through a mill levy for the repayment of a single issue of limited tax bonds, and refunding of such bonds, without any extension of the original bond term, so long as there is a net present value savings from the bond refunding (after considering costs of issuance) of at least 3%.

I also found, for the purpose of trying to define what bonds mean in relation to the University of Utah, in Title 53B. State System of Higher Education chapter 13, Higher Education Loan Act, the definition of bonds.

“Bonds” means the bonds authorized to be issued by the board under this chapter, and may consist of bonds, notes, or debt obligations evidencing an obligation to repay borrowed money and payable solely from revenues and other money of the board pledged for repayment.

It seems clear that the University of Utah should not transfer the “savings” into a revolving fund and the money should be refunded to the taxpayers. However, to be fair, more study is needed regarding Title 53B. State System of Higher Education.

Whether it is TIF or Green Bonds, Utahns will be paying for it whether they want to or not. If a project is less than successful, the developers won’t be on the hook for it, Utahns will.

As you can see, Utahns need to be very careful about approving bonds for future projects. Another possible solution for the bond issue would be the

Pay As You Go- Another form of TIF financing is known as “pay as you go,” in which the government reimburses a private developer as incremental taxes are generated. This form of TIF requires a developer to absorb some of the risk, in that the developer is required to invest its own capital in infrastructure costs. The developer can only get repaid (an amount that typically includes interest) after the project delivers and begins to be absorbed by the market.

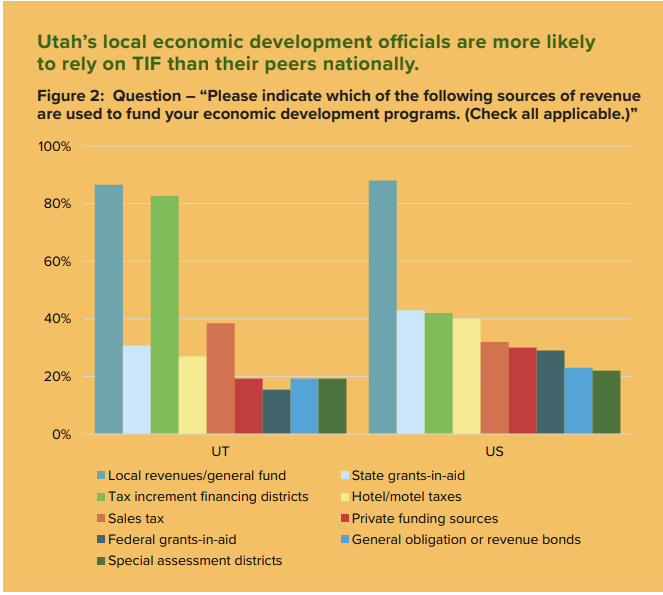

Cities and counties in Utah primarily rely upon general fund revenues (primarily funded via property, sales and business franchise taxes) and a mechanism known as tax increment financing (TIF) to pay for their economic development programs. Utah’s local economic development officials are nearly twice as likely as their peers nationally to use TIF.

Source: TIF as a funding source

The pay as you go model appears to be ideal. If the development is beneficial, then funding it would make sense. A developer would be more invested in projects that Utahns want rather than projects they don’t want. The developer would be on the hook if they tried to implement projects that the people did not want.

Our audience should take a deeper look into green bonds and how they work overall and in relation to our university system. This is a topic that will need time to research and unravel and another blog article may, later, emerge after thorough research has been completed.

At the end of the day, do not be discouraged, this process is extremely complicated and confusing. The language needs to be clear, concise, and transparent regarding how much money will be spent, where it will be spent, and what happens to excess dollars. The confusion behind what special districts are or are not, needs to be discussed. The people have questions that need to be answered and elected officials need to be able to discuss these issues without treating the public with disdain.